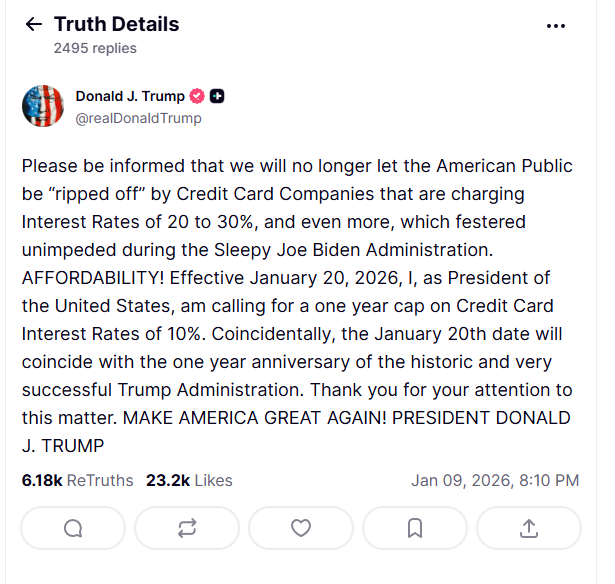

At a time when credit card interest rates routinely exceed 25 or even 30 percent, a proposed cap at 10 percent represents a meaningful shift for consumers. The difference is not theoretical. It is measurable, annual, and for many households, life changing.

Lower interest rates mean less money lost to compounding debt and more money that can actually be used to pay down balances, cover necessities, or be spent in the real economy. For anyone carrying revolving credit card debt, a 10 percent cap has the potential to put thousands of dollars back into their pocket over time.

That reality is exactly why banks are pushing back. When interest revenue disappears, it has to be replaced somewhere else.

When Donald Trump supported a 10 percent cap on credit card interest rates, banks ““Evidence shows that a 10% interest rate cap would reduce credit availability…If enacted, this cap would only drive consumers toward less regulated, more costly alternatives. We look forward to working with the administration to ensure Americans have access to the credit they need.”

What they are really saying is simple. If they cannot extract revenue through interest, they will look to recover it elsewhere. Most likely through higher merchant fees.

That does not change the outcome. Consumers still win.

How Banks Are Likely to Recoup Lost Interest Revenue

Credit card issuers have only a few levers they can pull.

They can reduce rewards, add annual fees, tighten underwriting, or increase interchange which raises merchant processing costs.

For consumers, this sounds concerning until you compare the math.

A reduction from 30 percent interest to 10 percent interest is a 20 percent swing in favor of the cardholder. That savings dwarfs any marginal increase in transaction costs passed through by merchants.

Why Passing Fees at Checkout Is Better Than Paying Interest Forever

Merchant fees are visible. Interest is not.

If interchange increases and merchants pass that cost back through a cash discount or small price adjustment, the consumer sees it immediately. It is a one-time cost tied to a single purchase.

On everyday purchases, the impact is small and transparent.

A $15 coffee with a 4% fee adds about 60 cents.

A $50 grocery run adds two dollars.

A $60 dinner adds roughly $2.40.

Interest charges work very differently. They compound quietly month after month and year after year. A consumer carrying a $10,000 balance can pay roughly $3,000 per year at 30% APR, compared to about $1,000 per year at 10% APR.

That difference alone puts $2,000 back into a consumer’s pocket every year.

Paying a few extra quarters or a couple of dollars at checkout is not comparable to losing thousands of dollars to compounding interest over time.

Transparency favors the consumer.

A Simple Example That Makes This Clear

Take a $10,000 credit card balance.

At 30 percent interest, that balance costs roughly $3,000 per year in interest alone.

At 10 percent interest, the cost drops to about $1,000 per year.

That is a $2,000 annual savings.

Even if higher merchant fees resulted in slightly higher prices or cash discount incentives, the consumer would still come out far ahead. The math is not close.

Lower interest puts real money back into consumers’ pockets. Merchant fees do not erase that benefit.

Why This Helps Merchants Too

When consumers pay less in interest, they have more disposable income. That money does not disappear. It gets spent.

Merchants benefit from:

- More completed transactions

- Higher approval rates

- Healthier repeat customers

- Less financial stress driving chargebacks or defaults

Merchants also retain control. Processing costs can be managed through pricing strategies that already exist. Interest charges cannot.

Banks Should Manage Risk Without Using Consumers as Insurance

Banks often imply that high interest rates are necessary to offset defaults. In reality, they rely on consumers paying 30 percent APR to cover losses from risky lending decisions.

If risk needs to be reduced, it should be done through smaller credit limits, better underwriting, and responsible lending practices. Not by trapping consumers in unpayable debt.

Lower interest forces better discipline. That is a good thing.

The Bottom Line

Even if banks raise merchant fees to compensate for lower interest revenue, consumers are still far better off.

A 20 percent reduction in interest rates saves far more money than any reasonable fee increase passed through at the register. Cash discounts and transparent pricing are a small price to pay for escaping long term debt cycles.

Lower interest keeps money in consumers’ pockets. More money in consumers’ pockets means more spending.

That is why this proposal works for consumers and merchants alike.